"Permanent Crisis"

I have a new piece in The Baffler about how to understand more than 45 years of rising overdose deaths.

It can be funny to talk about how magazine essays and stories come about. People ask me how and I just kinda throw up my hands go: Idk! A bunch of crazy shit just kinda lines up sometimes.

That’s the honest answer. These things can start from just the tiniest seed and over many weeks and months grow into thousands of words. Such is the case with my new essay in the latest print issue of The Baffler, titled “Permanent Crisis,” about the unrelenting 45+ year rise in drug mortality plaguing America. And how the CDC, politicians, policymakers, doctors, rely on an “epidemic” framework for treating and responding to substance use. By doing so, they are shoveling sand against the tide. Because they are trying to use health care to fix regulatory failures and market-driven behavior.

So, I’m going to talk about how this all came together. Before reading this you should probably goto The Baffler dot com and read that. You can also go to cool book stores and newsstands (if those still exist where you live) and find the beautiful print issue.

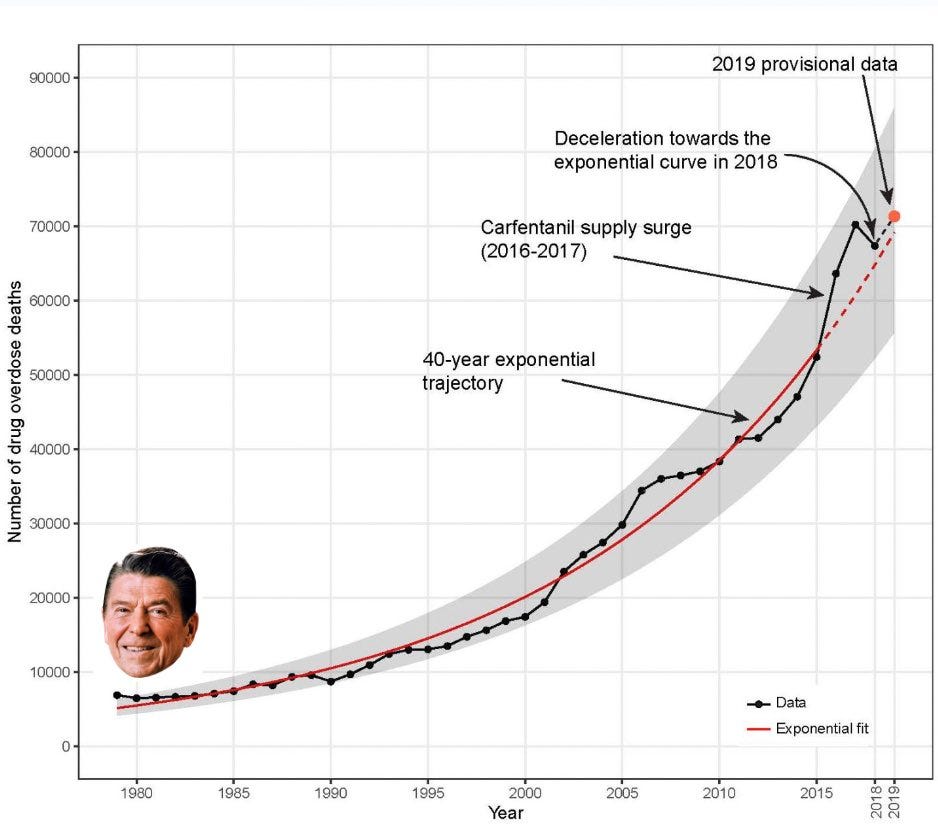

So here’s how it all started…. On Twitter, where else, I saw an account sharing a thread of charts where, in 1980, the the x-axis is stamped with a disembodied, grimacing face of President Ronald Reagan. And from there on, whatever is being charted, it goes off the rails. And then all you see is Reagan’s shit eating grin. It’s quite effective.

For example:

And….

I saw these charts and went, Oh!

This reminds me of a chart from a paper (known in my circles as the “Jalal and Burke chart”) that I saw a while back published in Science: “Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016.” The findings made a big splash in drug policy circles, producing a series of commentaries and responses to commentaries, and then responses to those responses and so on.

The paper found something explosive and sort of incredible (incredible in the literal sense, as in, hard to believe, not credible): From 1979 onward, drug mortality in the US rose exponentially. Deaths consistently rose 7 percent every year, doubling every eight to ten years. The data stayed on this course for more than four decades. And nothing else—not gun deaths, not suicide, not AIDS, not car crashes, not COVID—follows this exponential curve. Yes, there’s a few dips and wobbles here and there. But it seems—despite whatever policy or treatment or drug du jour—that deaths stubbornly snap back to the curve and start climbing up again, and again, and again.

So, a good story needs a twist. I needed more than: Hey things are bad, look at this chart! There has to be some conflict. A wrinkle. A nugget. Something spicy. Unexpected. In stories, I tend to look for ambivalence. Things that mean multiple things, maybe appear to be contradictory, that get to the core of something dense and difficult and maybe makes us a little uncomfortable to look at for very long and we’d rather not think about it.

I’m normal…..

I then remembered something I heard through the grapevine (reporters, investigators, detectives, nosey gossipers—we love the grapevine). I heard from sources that lawyers repping Purdue Pharma really liked this Jalal and Burke chart. Now that’s interesting. A chart that shows Americans dying in droves from drugs is loved by the most loathed pharmaceutical company in the world?

Why?

Because the chart casts a modicum of doubt that it was the company’s actions that set off a chain reaction of opioid prescriptions that gathered into a nuclear explosion of death. See, if deaths were already rising after 1979—many years before OxyContin came to market in 1996—then how could you pin the blame of a “drug epidemic” on Purdue and OxyContin? (I’ll get back to that in a sec…)

I tried to contact Purdue’s lawyers. That proved difficult. I don’t think they like reporters. With radio silence from their camp I couldn’t actually confirm that the lawyers used the chart in court to defend the Sacklers and Purdue. There’s so many cases, filings, hearings, etc. that it felt quite hard to pin this little rumor down. How could I connect the Jalal and Burke chart to the Sacklers?

I dug around until I found something.

The Sackler family hired a PR firm to push back against a tsunami of negative press balming the opioid crisis squarely on OxyContin and Purdue. And it just so happens, the chart where time begins in 1979 and deaths rise and rise appeared in a Sackler PR offensive titled “Judge For Yourselves.” You can slap Reagan’s face on the x-axis of the chart, which, in this context, is transposed into a defense of the Sackler family.

Good stories have irony. Isn’t it a tad, well, rich that the Sackler family—whom I describe in the piece as “the epitome of contemporary capitalist villainy”—use a chart where time begins in 1979 to try and absolve the company and the family of any wrongdoing?

In my mind, I’m thinking: My goodness, the chutzpah of this family!

In the story, I get into why Jalal and Burke’s chart creates something of a paradox. A contradiction. How a family of billionaires profiting off of addictive drugs can see the chart as absolution, and how others (ahem, me) see the chart as an indictment of the Sacklers and the social, political, eocnomic order of the last 50 years.

I wrote in the piece:

“Purdue was right about something. Drug mortality in America neither begins nor ends with the company’s actions. What pharmaceutical manufacturers, drug distributors, insurance companies, doctors, and pharmacies—the entire profit-mad medical system—collectively accomplished was to accelerate a train that was already speeding off the rails. But it’s hardly an absolution to argue that you did not start the fire, only poured gasoline on it for personal gain. With corporate power unchallenged and regulators asleep at the wheel, drug markets, like so many other consumer markets, have become more deadly, more dangerous, and, despite decades of aggressive and costly drug enforcement, more ubiquitous.”

Connecting the dots and synthesizing a lot of information into something coherent is how a magazine piece comes together.

And this one came together because I made my own stupid grimacing Reagan chart using Jalal and Burke’s exponential curve to show that something is rotten in Denmark. Maybe America isn’t plagued by the bad luck of sucessive drug epidemics that seemingly never stop no matter what drug du jour happens to be ripping across the nation. Here’s my own little shit eating grin Reagan chart.

And here is how the wonderful artists and illustrators at The Baffler turned into something way more fun and interesting:

So, I proceeded to write the piece, connecting the dots, blending reportage, historical analysis, interviews with historians, knowledge of statistics and epidemiology, interviewing statisticans and epidemiologists—all in service of throwing a wrench in the conventional wisdom that today’s “drug epidemic” began with OxyContin in 1996. And that, maybe, there is no opioid epidemic at all. That to think there is an opioid epidemic is to wrongly believe that this policy or that treatment can get a grip on the opioid market, tighten it, control it, and that somehow, some way, this long death curve will reverse itself. What if this reliance on the “epidemic” framework actually keeps leading us down a dead end? What if, in order to actually respond to this crisis, and actually bring it to heel, we need to use a different framework with new ideas?

Here’s where I land:

The current rhetorical, legal, and medical framework is simply no match for the deep malaise driving the problem. Root causes are downplayed, millions are left untreated, and thousands of preventable deaths are unprevented. We need a stronger, more expansive paradigm for understanding the exponentially increasing number of overdose deaths. A new language of substance use and drug policy that encompasses, and is responsive to, market dynamics and the social dysfunction to which they give rise. A consumer-protection model that does not criminalize the suffering, but also addresses the anxiety and dread that leads to compulsive, chaotic, and risky substance use. There must be something beyond, on the one hand, prohibition by brute force, and on the other, free-for-all drug markets ruled by profit. How can we create a world where people don’t need to use drugs to cope, or when they do use them, whether for relief, enhancement, or plain old fun, the penalty isn’t addiction, prison, or death?

Thanks, as always, for reading. And if you like what I do here, consider a paid subscription to keep this train running. I’d also like to thank the Economic Hardship Reporting Project for supporting my work.

YES. I am so excited to read your Baffler piece. This is right on.

“How can we create a world where people don’t need to use drugs to cope, or when they do use them, whether for relief, enhancement, or plain old fun, the penalty isn’t addiction, prison, or death?”

The answer to that question is what eludes us for the many reasons you outlined so well. What if?