Riding the Wave: From Pharma Opioids to Fentanyl

Drug users from Dayton, Ohio explain how they transitioned from prescription opioids to heroin and, eventually, to fentanyl.

The following quote comes from a person in Dayton, Ohio, who first used prescription opioids at the age of 23, then switched to heroin at the age of 32, and then transitioned to fentanyl at the age of 47. Nearly half of this person’s life has been spent navigating America’s volatile and ever-changing opioid markets:

“...I was prescribed 80 milligram OxyContin (90 pills per month) and I was given 60 milligram morphine (120 pills per month) for breakthrough pain for about two and a half years. And then the change came around [prescription monitoring programs] and they took me off all of that. I was given Percocet 10, three or four times a day. So, I started buying them [prescription opioids] off the street.”

The above quote captures how people’s drug use is shaped, molded, and determined by complex forces in society well beyond their control. In this case, the switch from medically prescribed opioids to street opioids after being cut off by doctors and losing access. The quote comes from a new qualitative study published in the journal Social Science and Medicine, which set out to analyze the way people moved through the various “waves” of America’s overdose crisis (prescription opioids > heroin > synthetics).

What the study lacks in sample size (N=60) it makes up for in vivid texture (to be sure, 60 interviews is a lot for a qualitative study). Reading through people’s reasoning and rationale for switching from pharma opioids to heroin and then, eventually, to fentanyl, I was reminded of the heated debates around 2016. The basic contours of the debate were: One side arguing to drastically and rapidly reduce opioid prescribing across the board. The other side was basically horrified and said, “No! You can’t just slash opioid prescribing and expect a clean outcome.” As opioid prescribing steeply declined, overdoses involving heroin surged. And the new debate was: “Well, you can’t pin the surge in heroin overdoses on the reduced prescribing.”

Now I think most people understand the two are deeply connected, and it’s almost common knowledge that rapidly reducing access to pharma opioids created a surge in the use of illicit opioids. But not long ago, there really was a moment when people doubted this connection. At the very least, the experience of people in Dayton now definitely confirms that the culture of “de-prescribing” contributed to a surge in heroin use, fentanyl use, and a steep rise in mortality.

In the paper, particpants report the way de-prescribing catapaulted them to the street. Based on their experience, I think it’s more than fair to say that the freeze on prescribing seriously contributed to the acceleration and surge in overdose deaths.

What happend was: A lot of people who were prescribed opioids for a long period of time experienced a sudden and unexpected loss of their medication, and this put them at serious risk for illicit use and then overdose. Take the experience of one participant who started using prescription opioids at 14, tried heroin one time at age 23, and then initiated full-on into fentanyl at 28 (again, notice how half this person’s life, 14 to 28, was swept up by opioids):

“....I was 27. I had a habit of doing opioids since the age of 14. And at that time period I was being prescribed two OxyContin, 50 milligrams a day, and had been that way since the last ten years. And so that's when I started doing heroin. Then later on I found out that there was a methadone clinic. I kind of wish that I would have been more informed by my doctor...or the nurses, or somebody, would have known about a methadone clinic and would say, Hey, look, you know, you can at least go get it, go get methadone and you'd be all right.”

It’s shocking to read. The same doctors who were happy to prescribe absurd amounts of opioids seemed to have no issue kicking their patients to the curb, without any help or referrals for further treatment. To realize a patient is addicted and not offer any treatment or even educate them on their options, like methadone, is a serious violation of ethical medicine. I think the “culture of prescribing” contributed to this image of patients taking opioids as being a bunch of “doctor shopping” criminals who posed a liability to the physican’s license. The “culture of prescribing” that took root in the mid-2010s was no doubt rooted in some amount of stigma against addiction.

It’s hard to know what else explains the numerous participants who confronted god awful medical practices. One participant described getting “fired” by her doctor over a drug test that popped up positive for other substances.

“It’s devastating [being terminated by the doctor] and it leaves a lot of us women up to extreme circumstances just to stay well and take care of our family. You know, that can be the difference between being a prostitute and not.... Yeah, that was basically it. We're not seeing you anymore. And then they said that I had a chance to potentially come back if I passed the drug test the next month, but that's kind of what leads you into just becoming an addict, because you find out how easy it is to get on the streets, and you can have and do as many as you want without worrying about that.”

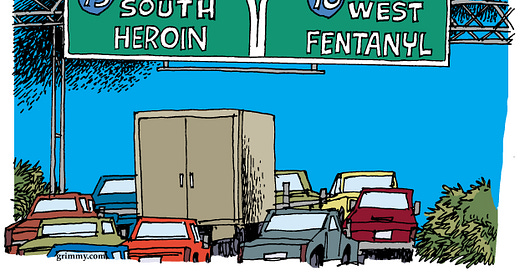

It’s really dark to read about what happens to people who are abandoned by their doctors. Once they’re kicked out of the medical system, people found themselves navigating street markets for the first time. This ultimately set up the transition from Wave One (pharma opioids) to Wave Two (heroin). And if you press-play long enough, that initial exodus out of the medical system created the conditions for the deadly synthetic wave. Once people were buying heroin on the street, it wouldn’t be long until that heroin turned into fentanyl.

The Culture of “De-Prescribing”

So how did all of this happen? Why were so many people prescribed to opioids suddenly kicked to the curb?

By 2016, there was a full-on government blitz to reduce the flow of pharmaceutical opioids. CDC Prescribing Guidelines were written, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs had vastly expanded, and there was an overall cultural and attitude shift toward the notion that prescription opioids were a terrible way to treat pain long-term, and there was this image that everyone who was on prescribed opioids for a long time was addicted to them, or selling them, or in some way was a nefarious actor. They were viewed as patients and then quickly seen as shady.

What sealed the deal was a big push for more muscular drug enforcement. The DEA started investigating high volume prescribers who prescribed above the recommended dosage spelled out in the CDC Guidelines. That led to raids on pain clinics (often derided as “pill mills,” which no doubt, some of these places, ahem, Florida, were totally criminal!)

The raids on clinics resulted in a lot of patients losing access to their medications. After clinics shutdown, as many warned, overdoses and mortality surged. Kevin Sabet, a former drug policy official in the federal government, bluntly stated that the government was fully aware that crackdowns on pharma opioids would cause a surge in heroin use. Here is what Sabet told a reporter (and friend) Jason Cherkis:

“We always were concerned about heroin. We were always cognizant of the push-down, pop-up problem. But we weren’t about to let these pill mills flourish in the name of worrying about something that hadn’t happened yet. … When crooks are putting on white coats and handing out pills like candy, how could we expect a responsible administration not to act?”

See how Sabet narrowly framed the options? Either do nothing about pill mills and let them flood communtiies with opioids, or shut them down and create a new generation of heroin users. Why were these only two options? Either way, what happened next was a disaster that we’re still reeling from. Opioid use in the medical realm rapidly declined, as overdoses in the street skyrocketed. Right around 2016, as the blitz on prescribing was full throttle, you can see that opioid prescribing became inversely correlated with overdoses.

By 2019, the harm that closing clinics caused patients was so severe that the FDA issued a warning against cutting patients off from prescription opioids. In 2022, KFF Health News published a startling investigation into the aftermath of pain clinic closures. Here is what the director of substance use research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health said about clinic closures in that story:

“We know that when you stop prescribing opioids, some people end up with death from suicide, overdose, increased illicit opioid use, pain exacerbations. It’s really important to have a continuity, and that is not really possible in the current opioid-prescribing culture.”

The prescribing culture. That’s what gets us back to this paper in Social Science and Medicine that I’ve been really into this week. A lot of research on opioid use typically focuses on personal motivation and individual characteristics. This paper emphasized not only the personal, but the array of impersonal factors, like federal and state drug policy, institutional medical practices, and broader changes in the drug supply— all shaping people’s habits and patterns of consumption.

Wave Two to Wave Three

The transition from Wave One to Wave Two—that is, from prescription opioids to heroin—is now fairly well documented. Now I want to focus a bit more on the transition from Wave Two (heroin) to Wave Three (synthetic opioids, fentanyl). We don’t know as much about that transition and how people navigated it. And that’s a pretty big blindspot, considering that more than two-thirds of overdose deaths today now involve synthetic opioids, mainly illicit fentanyl sold in pill and powder form.

The article, comprising 60 interviews of Dayton, Ohio residents, provides an excellent demonstration of a point that I think a lot about: That substance use is highly contigent on where you live and when you live, and that there are numerous factors that influence people’s drug use that go beyond personal and individual motivation. That’s especially true when it comes to fentanyl. I think a lot about this in my own life, and how by sheer luck and randomness I dodged the fentanyl bullet. Because I was a teenager in the early 2000s, I was exposed to pharma opioids like OxyContin instead of counterfeit pills that surley would’ve killed me, and probably, my entire school. It’s just pure chance.

It helps to know some basic information about the people interviewed for the study at-hand. The table below shows a demographic breakdown of the 60 interviewees in Dayton, which lies in Montgomery County, which for years has had the second highest overdose fatality rate in the state of Ohio (63.5 per 100,000; that’s almost double the national average about 32.4 deaths per 100,000).

As expected for Ohio, the participants are mostly white, ages 30 and older. More than half did not goto college and many are low-income. Over half of participants reported histories of multiple types of trauma: “contentious divorces/break-ups, physical and sexual abuse, the death of close friends and family, and serious car accidents.” For many, opioids were a way to manage physical pain and cope with internal psychic pain.

Fentanyl Initiation

One of the first things I noticed reading about people’s fentanyl use is that many of them, at first, did not want it nor ever ask for it. In fact, some had no idea what fentanyl even was! Thus, illicit fentanyl did not not arise out of consumer demand, instead it was thrusted upon many as a product of supply-induced demand:

“Participant accounts of their initiation into fentanyl support previous research, suggesting that the emergence of fentanyl is related more to supply-led changes in the heroin drug market than demand-led preferences.”

The Dayton users report that they were mostly blindsided by fentanyl. Many were using it without even knowing they were using it. To show how chaotic and unpredictable the market is, one participant reportedly thought the powder they were buying was cocaine:

“...it was a white powder, so you’re like okay, cocaine. But like he got addicted to it, I got addicted to it. My friend was like your boyfriend’s doing fentanyl. I'm like, what the hell is fentanyl? Like I don't know what the hell that fentanyl is...So we didn’t knowingly go out and do it [fentanyl].”

For many others, one day the heroin they were buying was adulterated with fentanyl. The greyish, brownish, chunky powder they were used to (heroin) eventually turned fluffy and white (fentanyl). Fentanyl then took over the entire Dayton market and users had no recourse. Some tried to dodge fentanyl by looking for prescription pills, but many realized the pills they were buying on the street was also just fentanyl pressed into pill form.

People were trapped.

The paper also discovered a novel initiation into fentanyl use. One might suppose that people went from pharma opioids to heroin and then found fentanyl. But the paper reveals that some people skipped the second wave entirely and made the leap from pharma opioids straight to fentanyl, by way of counterfeit pills.

It makes sense if you think about it: There is a stigma against purchasing a baggie of mystery powder on the street. So those who were taking pharmaceutical opioids and then—for various reasons—lost their supply, they started buying counterfeit pills and eventually realized they had been doing fentanyl.

The paper also highlights how fentanyl supercharged the risk of overdose and mortality.

“Initiation into fentanyl was associated with overdose experiences, with many participants reporting that they never overdosed until they used fentanyl. Overdoses commonly occurred when participants were unprepared for the potency of fentanyl and used the same amount as they typically would for heroin. In other instances, overdoses occurred when someone had a period of non-use and was unaware that the illicit opioid drug market contained adulterated heroin.”

Participants also described their first experience using fentanyl, if they remember it at all, and they conveyed how intensly potent it was compared to what they had been using prior. It shows just how unprepared people were for the fentanyl takeover, and how this lack knowledge coupled with extreme potency tragically led to a massive jump in mortality.

Below, one participant was given instructions on how to divide their fentanyl into tiny, minuscule lines, and they still wound up using too much:

“Well, I thought I got ripped off, like my buddy, he comes and gave me just a little bit. I only had a little bit of money at the time and I bought like $30 off of him or something. And he's like... “Don't do, don't do that much.” And he's like, “Lay it all out and cut it. Like in four fours, you know.” And he's like, “And that still might be a little too much.” I did that, cut it into fours and I did like one quarter of it. And I fucking passed out in my mom and dad's bathroom. Busted my lip open and shit on the sink and was just fucked up.

I think one of the main takeaways from this paper is that the way the American government has implemented its drug policy caused serious and deadly harm to millions of people. First, the entire medical system brokedown and regulators were asleep a the wheel as opioid prescribing rose to obscene levels. Then, realizing too many opioids were flowing, the government put the squeeze on the pharmaceutical supply, and that created an even deadlier problem in the illicit markets. And then along came fentanyl, which lit the match that set this powder keg ablaze.

The other takeaway, I think, is about the sheer complexity of the problem at hand. People’s drug histories and trajectories contain a multitude of factors and variables. The paper highlights the influence of familiy and peer networks peers on one’s drug use, as well as the role personal trauma plays. Then, there’s also much broader environmental and sociopolitical influences that shape the arc of one’s drug use. In order for America to get a grip on containing this blazing fire of overdose mortality, it’s crucial to understand how people get started on opioids, and then what takes their use to levels that are extremely risky and deadly.

I’d like to end this post with a helpful table that shows the transition through the various waves of opioid use. The table helps us understand the confluence of market, individual, and social factors that influenced people’s pattern of use.

great piece!